Oliver Laric – Sun Tzu Janus

Oliver Laric is among the most innovative and influential artists of his generation. Known for his work exploring questions of authorship and originality in the age of digital reproduction, his artwork started to be shared on blogs and websites in the early 2000s, associating him with what became termed Post Internet Art.

Image of artworks Gaslighting by Hannah Perry and Sun Tzu Janus by Oliver Laric, photographed by Beth Davis.

Oliver Laric came to prominence as the co-founder of the influential art blog, VVORK (2006-2012), which along with artist friends Aleksandra Domanovic, Christoph Priglinger and Georg Schnitzer quickly gained popularity amongst artists and arts professionals looking at art online. The blog was a kind of evolving depot of ideas: images, conversations - between works as much as between visitors - proliferated at VVORK, moving in and out of IRL space as circumstances suited. The site which was created one image at a time has come to be interpreted as existing between a museological artefact, and a futurological omen; like Janus, looking both forward and backward a multivalent perspective often adopted by Laric in his works.

787 Cliparts, 2006 by Oliver Laric

Laric’s interest in the potential of the archive in web-based cultures has proven to be among the post-prescient aspects of his art.

787 Cliparts for example, a video work composed entirely of free to use and distribute clip art images prefigured contemporary concerns about the use (and abuse) of digital imagery. Laric’s principled deployment of these images had both discursive and material implications. In discussion of the work, Laric eloquently has defended the importance of the free circulation and distribution of digital imagery - linking this imperative to the significance of sampling in the early days of hip hop music. The tragic foreclosure of the free sampling culture by artists - and more often record labels - chasing royalties for the use of minuscule snippets of their work prefigured today’s increasingly enclosed internet. Laric himself was forced to put his own reputation on the line in defending free circulation when an advertising agency produced a ‘reconstructed’ version of the work using clip art they had produced. The thorny grounds around open source culture and IP became a kind of legal no-man’s-land for the work.

Versions from 2009 powerfully anticipates the present moment of potentially infinite reproduction by machine learning and seeing processes. Laric’s video essay, in part scripted by himself and in part composed of pilfered and remixed language by other writers features scenes and images from various popular and fine art works, presenting them often in parallel to highlight apparent similarities, while speaking of the ways in which similarity and difference, presence and absence manifest over time and the passage of ideas from one mind and hand to others. As the robotic voiceover of the work notes ‘there is more work in interpreting interpretations than in interpreting things.’ These interpretations begin to speak to each other, and Laric’s works seek to find ways for this dialogue to be made visible.

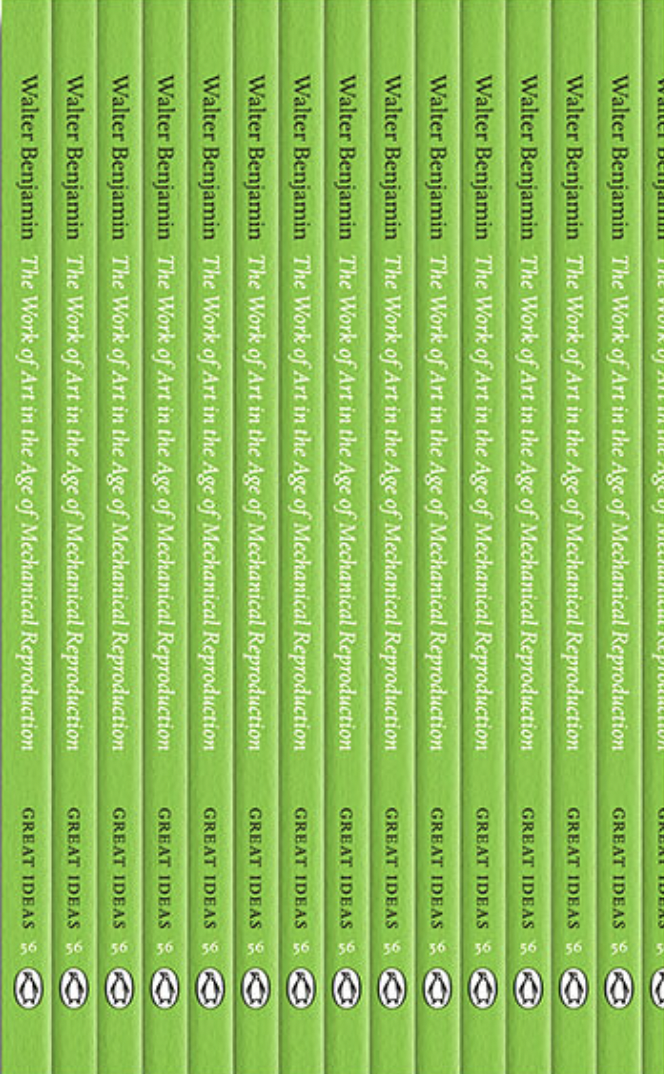

‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Walter Benajmin (1935)

Laric draws influences from a range of sources both artistic and literary. The iconic image of a Madonna and child repurposed as an image of Lady Justice described in ‘Versions’ - in which the Infant Jesus had been removed by iconoclasts and replaced by a scale - is among the most widely known examples of Laric’s aesthetic dialogues.

To view Laric’s works is to seek their context, and invite interlocutions. In the spirit of this omnivorous range of influence, one may take Walter Benjamin’s classic essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ and Marx’s ‘Fragment on Machines’ from The Grundrisse as generative contextual touchstones for thinking about Laric’s concerns.

In the case of Benjamin’s essay, Laric’s fascination with the ways in which images circulate and become recontextualised, remixed to use the language of hip hop, suggests that the aura of a work of art is not as intrinsically material as Benjamin suggested. While Benjamin sought the place of the physical contact between artwork and artist, Laric examines the unique perspective and cognitive relationships that emerge in digital cultures: the aura of the work of art is far from fading in this new context, but it is polymorphous and polysemous. Marx’s reflection on the capacity for machines to affect understandings of labour and value offers a way of thinking about Laric’s thinking about the ways in which art communities value works. The artistic object is no longer simply reducible to a physical entity placed in space, but it is a set of associations, artistic labour and artistic meaning inhere in the process of propagating and directing these evolving associations and meanings. The artist and the work are never static or fixed.

Sun Tzu Art of War City, Huimin

Laric’s sculpture Sun Tzu Janus from 2012 has become something of a centrepiece for the Shoreditch Arts Club. The artwork, generously on loan from a local private collection, attracts curiosity and attention from visitors and members alike.

The work establishes a rich dialogue with both art historical concerns, philosophical history, and contemporary discursive subject matter. From an art historical perspective, the work evokes Daniel Spoerri’s concept of the multiple, examining the aesthetic and value dynamics of production, reproduction, and originality.

Sun Tzu Janus incorporates two highly replicated artistic forms, the celebratory bust, and the votive image. The work is simultaneously a sculptural bust of Sun Tzu, the Chinese military philosopher and author of The Art of War who died 496 BCE, and a depiction of Janus, the Roman deity, “of all beginnings”, a reference to images of the god typically displayed at gates and doorways. The god is regarded to have been a protector in times of transition, especially in times of war.

Laric’s sculpture, produced in 2012, emerged at a highly specific moment in the evolution of contemporary art. The global economic crisis of 2007-8 was still reverberating throughout the global economy, amidst a febrile political climate defined in part by the uprisings throughout the Middle East - the so-called “Arab Spring” - and an American election cycle defined then, as is now common, ‘the most important election of our lifetimes’. That moment was also characterised by the advance of Web 2.0 platforms, particularly smartphones and social media, as indispensable features of everyday life. Looking back on the work from the perspective of a decade, its dialogic character feels profoundly present. The return, for example, of Sun Tzu as a favourite of messageboard posters only reinforces the multiplicity of perspectives that is the hallmark of Laric’s works.

Sun Tzu Janus, 2012 by Oliver Laric

The eyes of the pseudo-Sun Tzu gaze upon the viewer as the viewer returns its gaze. There is both no beginning and no ending to the discursive exchange. Like the early pieces that appeared on VVORK or the Madonna reboot spoken of in Versions, Sun Tzu Janus, presides over a geography of transitions, and of possibility.

Text by William Kherbek. Oliver Laric’s Sun Tzu Janus is generously on a long term loan from a local private collection. To see the work please get in touch with our membership team.